The largest island in Sydney Harbour, Cockatoo Island has a long and complex history, including use as an Indigenous fishing base, a penal establishment, a reform school and shipbuilding yards. Extensive quarrying and reclamation has expanded the island from 12.9 to 17.9 hectares and it now includes “constructed cliffs, stone walls and steps, docks, cranes, slipways and built forms”. The island provides a rich and dense accretion of buildings and structures that evoke a complex and layered history.

Cockatoo Island has been publicly accessible since 2005 and has a wide range of contemporary uses, which draw on, complement and reinterpret the site’s heritage. They include holiday accommodation, camping, hospitality and events, sport and recreation, as well as a site for temporary installations for the Sydney Biennale and other ephemeral events.

Cockatoo Island is managed by the Sydney Harbour Federation Trust (SHFT), a selffunding agency established by the Federal Government to protect the heritage and maximise public access to former defence and Commonwealth sites around Sydney Harbour.

Download a printable version of the Cockatoo Island case study (PDF 352 KB).

Site history and heritage

European occupation dates from 1839, when the island became a penal establishment. Convicts quarried stone for use elsewhere and also built structures on the island – including stone prison barracks, a military guardhouse, granary silos, official residences, maritime workshops and the Fitzroy Dock. Convict use ended in 1869 and the island housed an industrial school for orphan girls in 1871 with a separate reformatory for ‘delinquent’ girls. Orphan boys were housed offshore in an old hulk. It became a gaol again from 1888 to 1908.

Shipbuilding began in 1870 and continued in varying guises until the 1980s, by which time it was in serious decline. The island was finally vacated in 1992. In 2003 the SHFT proposed it be developed with a mix of uses including “working maritime site and as a functioning, active part of Sydney’s cultural life”.

Cockatoo Island is on the National and Commonwealth Heritage Lists. It was inscribed on the World Heritage List with ten other historic convict sites in 2010. It is significant as “the only remaining dry dock in Australia built using convict labour, as well as buildings and fabric related to the administration, incarceration and working conditions of convicts. Cockatoo Island also contains the nation’s most extensive and varied record of shipbuilding…”

Opportunities

Cockatoo Island is of outstanding heritage value and has a striking, unusual location. The SHFT saw the chance for a “maritime park to exercise the imagination”.

There was the potential for a wide range of adaptive reuse projects that would protect the island’s heritage, respond to its past and ensure a viable future.

Challenges

Many buildings and structures had deteriorated over time. Some were contaminated or contained other industrial hazards. The location meant that transporting materials, workers and visitors would be difficult. The size of the island, the large number and wide range of buildings on it and complex heritage overlays all presented further challenges.

Approach and outcome

Work is guided by the Cockatoo Island Management Plan, which provides “a long-term vision and a framework for decision making that is sufficiently flexible to accommodate new ideas and change and that is consistent with and does not adversely impact on the statutory heritage values of the place”. Much of the development is done directly by the SHFT, with some projects undertaken by external consultants and contractors.

The current adaptive reuse of sites and structures is consistent with the island’s history. The management plan states: “Traditionally, buildings on Cockatoo Island have been retained, reused and adapted to suit current needs. Periods of use overlapped and buildings were put to many different uses. Buildings, gardens, artefacts, ephemera, and most importantly the patina and historic layout are all still represented. Convict grain silos can be found side-by-side with a WWII search light tower, a steam powered crane with the convict constructed dock, and dockyard graffiti with the mercury arc glass rectifiers in the powerhouse. As a consequence, the island is a rich mosaic of all these things and is of exceptional heritage value.”

The island is organised into four precincts – the Southern, Northern and Eastern aprons and the Plateau – each with a different character. Each is being developed as a collection of complementary uses, with the spaces between buildings and structures understood as being as important as the fabric of the structures themselves.

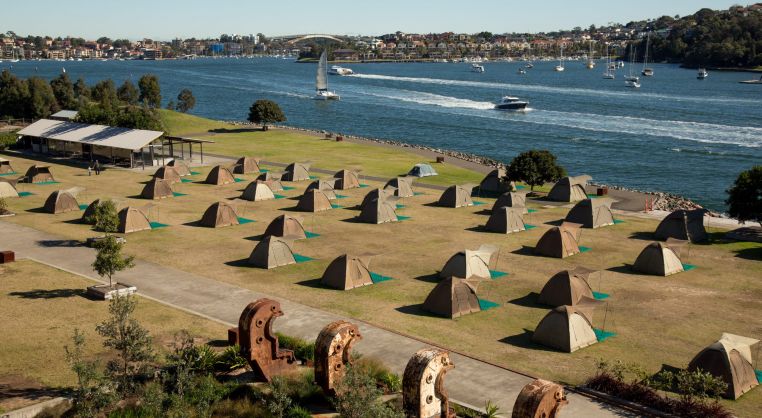

The Eastern Apron is the public access point. The Southern Apron focuses on new maritime uses within the existing building stock and hard stand. The Northern Apron – a large open space with remnants of previous industrial uses – has become parkland and incorporates a camp ground. The Plateau includes the gaol compound, rows of large, industrial workshops, and dwellings and gardens.

Large industrial workshops, such as the Mould Loft, are now spaces for meeting, events and temporary installations. A range of accommodation includes apartments in the Launch Driver and Coxswain’s houses, holiday houses in the former homes of the medical officer and engineering manager, camping and ‘glamping’. New recreational uses include a grass tennis court and an ocean netted swimming area in a historic slipway.

Lessons

- Public access and ongoing reuse is used as a way to protect and maintain the island’s heritage.

- Current and future reuses are understood as a continuation of the island’s long history of adaptation.

- The comprehensively researched Management Plan provides a coherent yet flexible framework for ongoing reuse, which is able to respond to new events and findings.

- The rich, aggregated history of the site is highly valued, with spaces between the buildings and juxtapositions understood as being as important as the fabric itself.